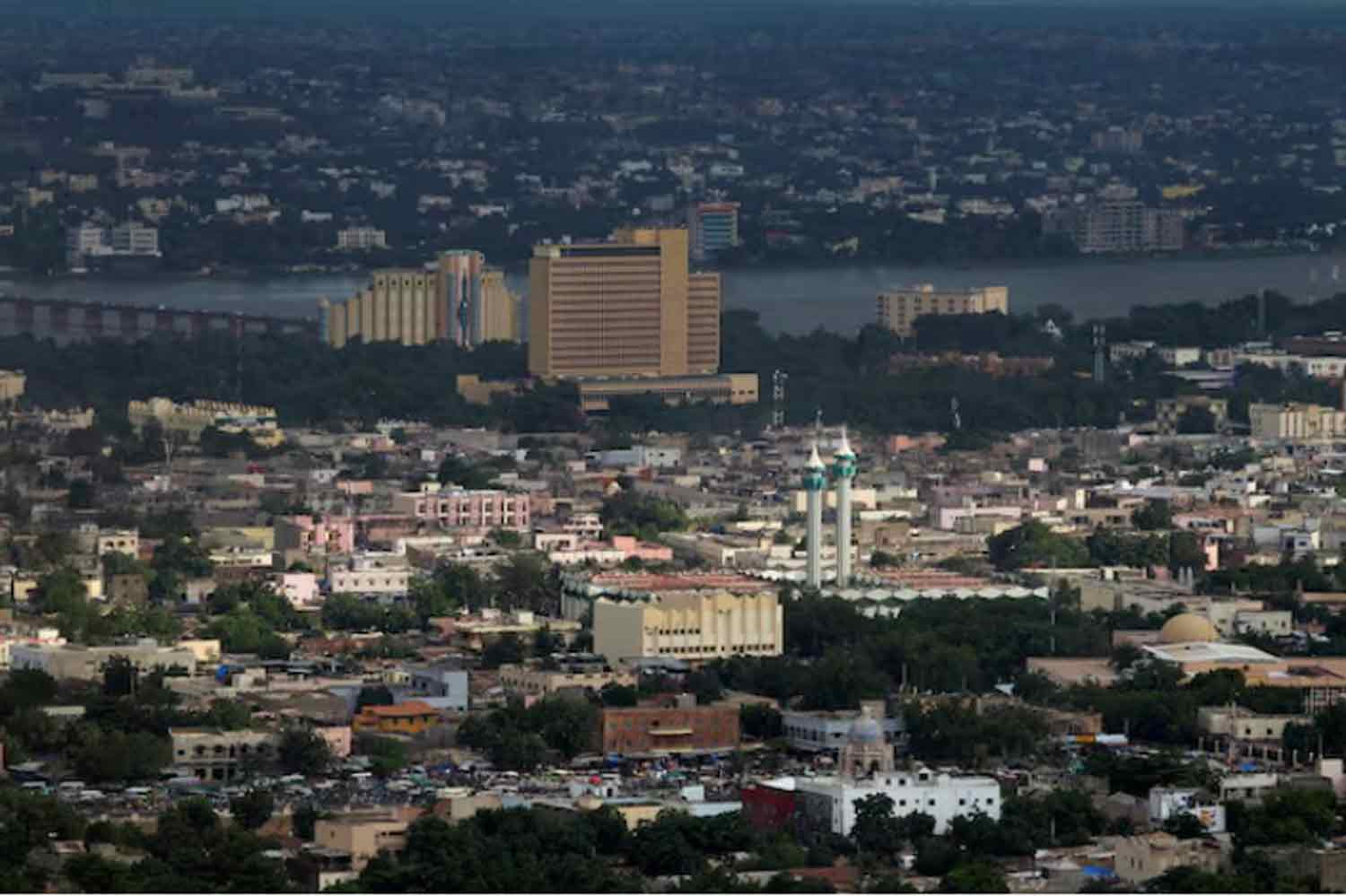

Weeks after infiltrating Mali’s capital unnoticed, the jihadis launched their attack just before dawn prayers. They targeted an elite police training academy, resulting in the deaths of numerous students, and proceeded to storm Bamako’s airport, where they set the presidential jet ablaze.

The assault on September 17 marked the most audacious attack in a Sahel capital since 2016, highlighting the capabilities of jihadist groups affiliated with al Qaeda or the Islamic State. These groups, which have primarily conducted rural insurgencies leading to the deaths of thousands and the displacement of millions in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, demonstrated their ability to strike at the center of power.

While conflicts in Ukraine, the Middle East, and Sudan dominate global news, the ongoing turmoil in the Sahel is contributing to a significant increase in migration towards Europe. This surge occurs amid a rise in anti-immigrant sentiments and tightening borders in several EU countries. The U.N.’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) reports that the route from West African coastal nations to Spain’s Canary Islands has seen the most significant increase in migration numbers this year.

Data from the International Organization for Migration indicates that the number of migrants arriving in Europe from Sahel nations—specifically Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal—has surged by 62%, reaching 17,300 in the first half of 2024, compared to 10,700 during the same period last year. This increase has been attributed by both the United Nations and the IOM to ongoing conflicts and the impacts of climate change.

Fifteen diplomats and experts informed Reuters that the extensive areas controlled by jihadist groups pose a significant risk of becoming training sites and launching points for further attacks on major urban centers like Bamako, as well as on neighboring countries and Western interests in the region and beyond.

The severe impact of jihadist violence, particularly on government forces, has been a critical factor in the series of military coups that have occurred since 2020, targeting Western-supported governments in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, which are central to the Sahel region. The military regimes that have taken over have shifted their reliance from French and U.S. military support to Russian assistance, primarily from the Wagner Group, yet they continue to face territorial losses.

Caleb Weiss, an editor at the Long War Journal and a specialist in jihadist movements, expressed skepticism about the longevity of the regimes in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. “I don’t believe these governments can sustain themselves indefinitely. Sooner or later, one will collapse or lose significant territory, which has already occurred in Burkina Faso,” he stated. He warned that this could lead to the emergence of a jihadi state or multiple such entities in the Sahel region.

Western nations that previously committed resources to combat jihadist threats now find their operational capacity severely diminished, particularly after Niger’s junta expelled U.S. forces from a major drone base in Agadez last year. U.S. military personnel and the CIA had utilized drones for tracking jihadists and collaborated with allies like France, which conducted airstrikes against these militants, as well as with West African military forces.

However, tensions arose when U.S. officials refused to share intelligence with Niger’s coup leaders and cautioned against their engagement with Russian entities, leading to their expulsion. The U.S. is currently seeking alternative locations to reposition its assets.

Wassim Nasr, a senior research fellow at The Soufan Center in New York, noted that no other entities have stepped in to provide effective air surveillance or support, allowing jihadists to operate with relative freedom across these three nations. A Reuters analysis of data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) revealed that violent incidents involving jihadist groups in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have nearly doubled since 2021. This year alone has seen an average of 224 attacks per month, a significant increase from 128 in 2021.

Insa Moussa Ba Sane, the regional migration and displacement coordinator for the International Federation of the Red Cross, highlighted that conflict is a primary driver of increased migration from the West African coast, with a notable rise in the number of women and families observed along migration routes.

Conflicts are fundamentally intertwined with the challenges posed by climate change, leading to increased violence and a significant migration from rural to urban areas, he explained. In Burkina Faso, which is among the most severely impacted regions, jihadists linked to al Qaeda killed hundreds of civilians in a single day on August 24 in Barsalogho, located two hours from the capital, Ouagadougou.

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) in Sydney, Burkina Faso has reached the top of its Global Terrorism Index for the first time this year, with a staggering 68% increase in fatalities, totaling 1,907—representing a quarter of all terrorism-related deaths globally. The United Nations has reported that approximately half of Burkina Faso is now outside government control, contributing to escalating displacement rates.

“The two major veteran terrorist groups are expanding their influence. The threat is becoming more widespread,” stated Seidik Abba, president of the CIRES think tank in Paris, referring to al Qaeda and the Islamic State. A U.N. expert panel monitoring these organizations estimates that JNIM, the al Qaeda-affiliated group most active in the Sahel, has between 5,000 and 6,000 fighters, while 2,000 to 3,000 militants are associated with the Islamic State.

“Their stated objective is to impose Islamic governance,” noted Nasr from The Soufan Center. Jihadists employ a combination of coercion and the provision of essential services, such as local courts, to establish their governance systems in rural areas that have long felt neglected by ineffective and corrupt central authorities.

“Join us. We will spare your family. We will assist you and provide financial support,” recounted a man from Mali, reflecting on his experiences as a teenager with jihadists who attacked his village. “But they are untrustworthy, as they kill your friends right before your eyes.” The young man escaped to the Canary Islands last year before relocating to Barcelona, choosing to remain anonymous due to concerns for the safety of family members still in Mali.

Jihadi groups are active in various regions, occasionally engaging in conflicts with one another, although they have also formed localized non-aggression agreements, according to reports from U.N. experts. These groups receive financial backing, training, and strategic direction from their global leaders, while also imposing taxes in the territories they control and capturing weapons following confrontations with government forces, the reports indicate.

European nations are split on their approach to the ongoing conflict. Southern European countries, which bear the brunt of migrant arrivals, prefer to maintain dialogue with the ruling juntas, whereas others oppose this due to concerns regarding human rights and democratic principles, as noted by nine diplomats in the area. An African diplomat emphasized the necessity for the EU to stay involved, as the migration issue is unlikely to resolve itself.

Even if a consensus were reached among European nations, they would still face challenges due to insufficient military capabilities and strained political ties, as Sahelian countries are resistant to Western involvement, according to the diplomats. General Ron Smits, head of the Dutch Special Forces, remarked, “We do not have any influence in those countries on extremist groups.”

Western powers are also apprehensive about the possibility of the Sahel evolving into a stronghold for global jihad, reminiscent of Afghanistan or Libya in previous decades. General Michael Langley, head of U.S. Africa Command, stated that “all these violent extremist organizations do have aspirations of attacking the United States.” However, other officials and analysts contend that these groups have not expressed intentions to target Europe or the U.S. thus far.

Will Linder, a former CIA officer who now leads a risk consultancy, pointed out that the recent attacks in Bamako and Barsalogho illustrate the inadequacy of the juntas’ security measures in Mali and Burkina Faso. He asserted, “The leadership of both countries really need new strategies for countering their jihadist insurgencies.”

Discover more from Defence Talks | Defense News Hub, Military Updates, Security Insights

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.